What Kind of Film Did Critic Rick Altman Call the Most Complex Art Form Ever Devised?

A moving picture genre is a stylistic or thematic category for motion pictures based on similarities either in the narrative elements, aesthetic approach, or the emotional response to the film.[2]

Cartoon heavily from the theories of literary-genre criticism, picture genres are usually delineated by "conventions, iconography, settings, narratives, characters and actors."[three] One can too classify films by the tone, theme/topic, mood, format, target audience, or upkeep.[four] These characteristics are virtually evident in genre films, which are "commercial feature films [that], through repetition and variation, tell familiar stories with familiar characters and familiar situations" in a given genre.[five]

A film'due south genre will influence the use of filmmaking styles and techniques, such as the apply of flashbacks and low-cardinal lighting in moving-picture show noir; tight framing in horror films; or fonts that look like rough-hewn logs for the titles of Western films.[six] In improver, genres have associated movie-scoring conventions, such every bit lush string orchestras for romantic melodramas or electronic music for science-fiction films.[six] Genre as well affects how films are broadcast on idiot box, advertised, and organized in video-rental stores.[5]

Alan Williams distinguishes three main genre categories: narrative, avant-garde, and documentary.[seven]

With the proliferation of particular genres, film subgenres can as well emerge: the legal drama, for case, is a sub-genre of drama that includes court- and trial-focused films. Subgenres are often a mixture of two separate genres; genres can also merge with seemingly unrelated ones to form hybrid genres, where popular combinations include the romantic comedy and the action one-act film. Broader examples include the docufiction and docudrama, which merge the basic categories of fiction and non-fiction (documentary).[eight]

Genres are not fixed; they alter and evolve over time, and some genres may largely disappear (for case, the melodrama).[4] Not merely does genre refer to a type of film or its category, a key role is likewise played by the expectations of an audition about a film, too as institutional discourses that create generic structures.[4]

Overview [edit]

Characteristics [edit]

Characteristics of particular genres are most evident in genre films, which are "commercial feature films [that], through repetition and variation, tell familiar stories with familiar characters and familiar situations" in a given genre.[5]

Drawing heavily from the theories of literary-genre criticism, film genres are unremarkably delineated past conventions, iconography, narratives, formats, characters, and actors, all of which tin can vary co-ordinate to the genre.[3] In terms of standard or "stock" characters, those in flick noir, for example, include the femme fatale[9] and the "hardboiled" detective; while those in Westerns, stock characters include the schoolmarm and the gunslinger. Regarding actors, some may acquire a reputation linked to a single genre, such as John Wayne (the Western) or Fred Astaire (the musical).[x] Some genres take been characterized or known to use particular formats, which refers to the manner in which films are shot (e.one thousand., 35 mm, 16 mm or 8 mm) or the way of presentation (e.g., anamorphic widescreen).[4]

Genres can too be classified by more than inherent characteristics (unremarkably implied in their names), such every bit settings, theme/topic, mood, target audience, or upkeep/type of production.[four]

- The setting is the environment—including both time and geographic location—in which the story and activity accept identify (east.g., present day or historical period; Earth or outer-space; urban or rural, etc.). Genres that are peculiarly concerned with this element include the historical drama, war movie, Western, and infinite-opera, the names of which all denote particular settings.[four]

- The theme or topic refers to the issues or concepts that the film revolves around; for example, the science-fiction pic, sports movie, and crime film.

- The mood is the emotional tone of the picture show, every bit implied in the names of the comedy motion-picture show, horror film, or 'tearjerker'.

- Genres informed by particular target audience(s) include children's picture, teen film, women'southward film, and "chick flick"

- Genres characterized past the type of production include the blockbuster, independent film, and depression-budget moving-picture show, such as the B movie (commercial) or apprentice film (noncommercial).

Screenwriters, in particular, ofttimes organize their stories past genre, focusing their attention on 3 specific aspects: atmosphere, graphic symbol, and story.[11] A film's atmosphere includes costumes, props, locations, and the visceral experiences created for the audience.[12] Aspects of character include archetypes, stock characters, and the goals and motivations of the central characters.[13] Some story considerations for screenwriters, every bit they chronicle to genre, include theme, tent-pole scenes, and how the rhythm of characters' perspective shift from scene to scene.[14]

Examples of genres and subgenres [edit]

| Genre | Clarification | Subgenre(s) | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Action movie | Associated with particular types of spectacle (e.thousand., explosions, chases, combat)[15] |

|

|

| Adventure film | Implies a narrative that is divers by a journey (ofttimes including some form of pursuit) and is usually located within a fantasy or exoticized setting. Typically, though not always, such stories include the quest narrative. The predominant emphasis on violence and fighting in action films is the typical difference between the two genres.[15] [16] |

|

|

| Animated motion picture | A film medium in which the film's images are primarily created by computer or hand and the characters are voiced by actors.[17] Blitheness can otherwise contain any genre and subgenre[ii] and is often confused every bit a genre itself. |

|

|

| One-act film | Defined by events that are primarily intended to make the audition express joy |

|

|

| Drama | Focused on emotions and defined past conflict, often looking to reality rather than sensationalism. |

|

|

| Fantasy film | Films defined past situations that transcend natural laws and/or by settings inside a fictional universe, with narratives that are ofttimes inspired past or involve man myths. The genre typically incorporates not-scientific concepts such as magic, mythical creatures, and supernatural elements.[2] [17] |

|

|

| Historical flick | Films that either provide more than-or-less accurate representations of historical accounts or depict fictional narratives placed inside an accurate depiction of a historical setting.[2] |

|

|

| Horror film | Films that seek to arm-twist fear or disgust in the audition for amusement purposes.[18] |

|

|

| Noir film | A genre of fashionable criminal offence dramas particularly popular during the 1940s and '50s. They were oftentimes reflective of the American society and civilization at the time. |

|

|

| Science fiction film | Films are divers by a combination of imaginative speculation and a scientific or technological premise, making use of the changes and trajectory of applied science and scientific discipline. This genre often incorporates infinite, biology, energy, fourth dimension, and any other observable science.[2] [17] |

|

|

| Thriller film | Films that evoke excitement and suspense in the audience. The suspense element establish in near films' plots is particularly exploited past the filmmaker in this genre. Tension is created by delaying what the audience sees as inevitable, and is congenital through situations that are menacing or where escape seems impossible.[19] |

|

|

| Western | A genre in which films are set in the American W during the 19th century and embodies the "spirit, the struggle and the demise of the new frontier." These films will often feature horse riding, trigger-happy and not-violent interaction with Native-American tribes, gunfights, and technology created during the industrial revolution.[2] [17] |

|

|

History [edit]

From the primeval days of cinema in the 19th century the term "genre" (already in use in English with reference to works of art or literary production from at least 1770[twenty]) was used[ by whom? ] to organize films according to type.[21] By the 1950s André Bazin was discussing the concept of "genre" by using the Western film as an case; during this era, in that location was a debate over auteur theory versus genre.[4] In the late 1960s the concept of genre became a pregnant role of movie theory.[4]

Film genres depict on genres from other forms; Western novels existed before the Western film, and musical theatre pre-dated picture musicals.[22] The perceived genre of a moving-picture show tin alter over time; for example, in the 21st century The Peachy Train Robbery (1903) classes as a key early Western film, but when released, marketing promoted it "for its relation to the then-pop genres of the chase film, the railroad film and the law-breaking picture".[23] A key reason that the early Hollywood industrial system from the 1920s to the 1950s favoured genre films is that in "Hollywood's industrial fashion of product, genre movies are dependable products" to market to audiences - they were easy to produce and it was easy for audiences to empathize a genre film.[24] In the 1920s to 1950s, genre films had clear conventions and iconography, such equally the heavy coats worn by gangsters in films like Lilliputian Caesar (1931).[25] The conventions in genre films enable filmmakers to generate them in an industrial, assembly-line fashion, an approach which tin can exist seen in the James Bond spy-films, which all use a formula of "lots of activity, fancy gadgets, beautiful woman and colourful villains", even though the actors, directors and screenwriters alter.[25]

Pure and hybrid genres [edit]

Films are rarely purely from 1 genre, which is in keeping with the picture palace's diverse and derivative origins, it existence a blend of "vaudeville, music-hall, theatre, photography" and novels.[4] American film historian Janet Staiger states that the genre of a film can be defined in iv ways. The "idealist method" judges films by predetermined standards. The "empirical method" identifies the genre of a film past comparing it to a list of films already accounted to fall within a certain genre. The apriori method uses mutual generic elements which are identified in advance. The "social conventions" method of identifying the genre of a film is based on the accepted cultural consensus within order.[26] Martin Loop contends that Hollywood films are not pure genres considering most Hollywood movies blend the love-oriented plot of the romance genre with other genres.[26] Jim Colins claims that since the 1980s, Hollywood films accept been influenced by the trend towards "ironic hybridization", in which directors combine elements from different genres, as with the Western/science fiction mix in Back to the Future Part Iii.[26]

Many films cross into multiple genres. Susan Hayward states that spy films often cantankerous genre boundaries with thriller films.[four] Some genre films take genre elements from ane genre and place them into the conventions of a 2nd genre, such as with The Band Railroad vehicle (1953), which adds motion picture noir and detective film elements into "The Girl Hunt" ballet.[25] In the 1970s New Hollywood era, in that location was so much parodying of genres that it can be hard to assign genres to some films from this era, such as Mel Brooks' comedy-Western Blazing Saddles (1974) or the private eye parody The Long Goodbye (1973).[four] Other films from this era bend genres so much that it is challenging to put them in a genre category, such as Roman Polanski'due south Chinatown (1974) and William Friedkin'south The French Connexion (1971).[4]

Moving picture theorist Robert Stam challenged whether genres actually exist, or whether they are merely fabricated upwards by critics. Stam has questioned whether "genres [are] really 'out at that place' in the globe or are they actually the construction of analysts?". Too, he has asked whether in that location is a "... finite taxonomy of genres or are they in principle infinite?" and whether genres are "...timeless essences imperceptible, fourth dimension-bound entities? Are genres culture-bound or trans-cultural?" Stam has also asked whether genre analysis should aim at existence descriptive or prescriptive. While some genres are based on story content (the war film), other are borrowed from literature (one-act, melodrama) or from other media (the musical). Some are performer-based (Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers films) or budget-based (blockbusters, low budget film), while others are based on artistic condition (the art film), racial identity (Race films), location (the Western), or sexual orientation (Queer cinema).[27]

Audience expectations [edit]

Many genres have built-in audiences and corresponding publications that support them, such every bit magazines and websites. For example, horror films accept a well-established fanbase that reads horror magazines such every bit Fangoria. Films that are difficult to categorize into a genre are often less successful. As such, film genres are also useful in the areas of marketing, moving picture criticism and the analysis of consumption. Hollywood story consultant John Truby states that "...you take to know how to transcend the forms [genres] so y'all tin can give the audience a sense of originality and surprise."[28]

Some screenwriters utilise genre as a means of determining what kind of plot or content to put into a screenplay. They may study films of specific genres to observe examples. This is a fashion that some screenwriters are able to copy elements of successful movies and laissez passer them off in a new screenplay. It is likely that such screenplays autumn short in originality. As Truby says, "Writers know enough to write a genre script only they oasis't twisted the story beats of that genre in such a way that information technology gives an original face up to it".[29]

Cinema technologies are associated with genres. Huge widescreens helped Western films to create an expansive setting of the open plains and desert. Science fiction and fantasy films are associated with special effects, notably computer generated imagery (due east.yard., the Harry Potter films).[4]

In 2017, screenwriter Eric R. Williams published a system for screenwriters to conceptualize narrative film genres based on audition expectations.[xxx] The system was based upon the structure biologists use to analyze living beings. Williams wrote a companion book detailing his taxonomy, which claims to be able to place all feature length narrative films with 7 categorizations: moving picture type, super genre, macro-genre, micro-genre, vocalization, and pathway.[31]

Categorization [edit]

Because genres are easier to recognize than to ascertain, academics agree they cannot be identified in a rigid mode.[32] Furthermore, different countries and cultures define genres in different ways. A typical example are war movies. In US, they are mostly related to ones with large U.Due south involvement such as World wars and Vietnam, whereas in other countries, movies related to wars in other historical periods are considered war movies.

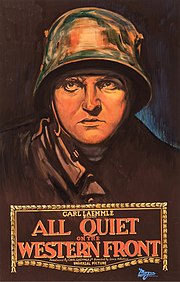

Film genres may appear to be readily categorizable from the setting of the film. Even so, films with the aforementioned settings can be very dissimilar, due to the apply of dissimilar themes or moods. For example, while both The Boxing of Midway and All Quiet on the Western Front are set in a wartime context and might be classified as belonging to the war film genre, the first examines the themes of award, sacrifice, and valour, and the second is an anti-war film which emphasizes the hurting and horror of war. While there is an argument that movie noir movies could exist accounted to be set up in an urban setting, in inexpensive hotels and underworld bars, many classic noirs accept place mainly in pocket-size towns, suburbia, rural areas, or on the open route.[33]

The editors of filmsite.org argue that animation, pornographic film, documentary film, silent film and then on are non-genre-based film categories.[34]

Linda Williams argues that horror, melodrama, and pornography all fall into the category of "torso genres" since they are each designed to arm-twist concrete reactions on the part of viewers. Horror is designed to elicit spine-chilling, white-knuckled, middle-bulging terror; melodramas are designed to make viewers cry after seeing the misfortunes of the onscreen characters; and pornography is designed to arm-twist sexual arousal.[35] This arroyo tin be extended: comedies make people laugh, tear-jerkers make people cry, feel-practiced films elevator people'south spirits and inspiration films provide promise for viewers.

Eric R. Williams (no relation to Linda Williams) argues that all narrative characteristic length films can be categorized as one of xi "super genres" (Activeness, Crime, Fantasy, Horror, Romance, Science Fiction, Piece of Life, Sports, Thriller, War and Western).[eleven] Williams contends that labels such equally comedy or drama are more broad than the category of super genre, and therefore autumn into a category he calls "motion picture type".[thirty] Similarly, Williams explains that labels such equally animation and musical are more than specific to storytelling technique and therefore fall into his category of "voice".[36] For example, co-ordinate to Williams, a movie like Blazing Saddles could be categorized as a Comedy (blazon) Western (super-genre) Musical (voice) while Anomolisa is a Drama (type) Slice of Life (super-genre) Animation (voice). Williams has created a seven-tiered categorization for narrative feature films called the Screenwriters Taxonomy.[31]

A genre motion picture is a film that follows some or all of the conventions of a item genre, whether or not information technology was intentional when the moving-picture show was produced.[37]

Film in the context of history [edit]

In guild to understand the creation and context of each film genre, we must look at its popularity in the context of its place in history. For case, the 1970s Blaxploitation films accept been called an attempt to "undermine the rise of Afro-American's Black consciousness movement" of that era.[4] In William Park's assay of film noir, he states that we must view and interpret moving picture for its message with the context of history within our minds; he states that this is how movie tin can truly exist understood by its audition.[38] Film genres such as motion-picture show noir and Western picture show reverberate values of the time catamenia. While film noir combines German expressionist filming strategies with post World State of war Two ideals; Western films focused on the ideal of the early 20th century. Films such as the musical were created as a form of entertainment during the Great Depression allowing its viewers an escape during tough times. So when watching and analyzing film genres we must remember to remember its true intentions aside from its entertainment value.

Over fourth dimension, a genre can change through stages: the classic genre era; the parody of the classics; the menses where filmmakers deny that their films are office of a certain genre; and finally a critique of the entire genre.[four] This blueprint tin exist seen with the Western motion-picture show. In the earliest, classic Westerns, there was a clear hero who protected guild from lawless villains who lived in the wilderness and came into civilization to commit crimes.[4] Withal, in revisionist Westerns of the 1970s, the protagonist becomes an anti-hero who lives in the wilderness to get abroad from a civilization that is depicted as corrupt, with the villains at present integrated into society. Another example of a genre changing over time is the popularity of the neo-noir films in the early 2000s (Mulholland Drive (2001), The Man Who Wasn't There (2001) and Far From Sky (2002); are these film noir parodies, a repetition of noir genre tropes, or a re-examination of the noir genre?[4]

This is also of import to recollect when looking at films in the future. As viewers lookout man a moving picture they are conscious of societal influence with the film itself. In order to sympathise it's truthful intentions, we must identify its intended audience and what narrative of our current society, also as it comments to the by in relation with today'southward society. This enables viewers to sympathise the evolution of flick genres as time and history morphs or views and ideals of the entertainment industry.

See also [edit]

- Film

- Glossary of motion picture terms

References [edit]

- ^ "America'southward 10 Greatest Films in 10 Classic Genres". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2010-06-06 .

AFI defines 'western' as a genre of films set in the American Due west that embodies the spirit, the struggle and the demise of the new frontier.

- ^ a b c d e f g "ninety+ Moving-picture show Genre Examples for Film & Television receiver". StudioBinder. 2020-12-13. Retrieved 2021-02-25 .

- ^ a b Grant, Barry Keith (2007). Film Genre: From Iconography to Ideology. Short cuts. Vol. 33 (reprint ed.). London: Wallflower Press. p. 2. ISBN9781904764793 . Retrieved 2018-10-13 .

[...] the various elements of genre films, including conventions, iconography, settings, narratives, characters and actors.

- ^ a b c d e f thousand h i j g l thou n o p q Hayward, Susan. "Genre/Sub-genre" in Cinema Studies: The Primal Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 185-192

- ^ a b c Grant, Barry Keith. Film Genre: From Iconography to Credo. Wallflower Press, 2007. p. 1

- ^ a b Grant, Barry Keith. Film Genre: From Iconography to Ideology. Wallflower Press, 2007. p. eleven

- ^ Alan Williams, "Is a Radical Genre Criticism Possible?" Quarterly Review of Moving picture Studies ix, no. ii (Jump 1984): 121-2

- ^ Judith Butler and genre theory.

- ^ Grant, Barry Keith. Movie Genre: From Iconography to Ideology. Wallflower Press, 2007. p. 17

- ^ Grant, Barry Keith. Flick Genre: From Iconography to Credo. Wallflower Press, 2007. p. 18

- ^ a b Williams, Eric R. "Episode iii: Flick Genre: It's Not What You Think". How to View and Appreciate Cracking Movies . Retrieved 2020-06-07 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ Williams, Eric R. "Episode iv: Genre Layers and Audience Expectations". How to View and Appreciate Great Movies . Retrieved 2020-06-07 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ Williams, Eric R. "How to View and Appreciate Great Movies (episode 18: Knowing Characters from the Outside In)". English . Retrieved 2020-06-07 .

- ^ Williams, Eric R. "Episode 5: Story Shape and Tension". How to View and Appreciate Great Movies . Retrieved 2020-06-07 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Activity and Adventure Films | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com . Retrieved 2021-02-25 .

- ^ "Adventure Films". www.filmsite.org . Retrieved 2021-02-25 .

- ^ a b c d "AFI's 10 TOP 10". American Film Establish . Retrieved 2021-02-25 .

- ^ "What is a horror flick? | Screenwriter". www.irishtimes.com . Retrieved 2021-11-06 .

- ^ Konigsberg, Ira (1997). The consummate film dictionary (2nd ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN0-670-10009-9. OCLC 36112196.

- ^ "genre". Oxford English language Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Printing. (Subscription or participating establishment membership required.)

- ^ Hayward, Susan (1996). "Genre/Sub-genre". Movie theater Studies: The Key Concepts. Routledge Key Guides (three ed.). London: Routledge (published 2006). p. 185. ISBN9781134208920 . Retrieved 29 May 2020.

As a term genre goes dorsum to earliest movie theatre and was seen every bit a style of organizing films co-ordinate to type. But it was not until the late 1960s that genre was introduced as a central concept into Anglo-Saxon film theory [...].

- ^ Grant, Barry Keith. Motion-picture show Genre: From Iconography to Credo. Wallflower Press, 2007. p. 4

- ^ Grant, Barry Keith (2007). "approaching motion-picture show genre". Film Genre: From Iconography to Ideology. Short cuts. Vol. 33. London: Wallflower Printing. p. 6. ISBN9781904764793 . Retrieved 29 May 2020.

[...] Neale notes that near histories of the western film begin with The Smashing Train Robbery (1903), but when released it was promoted not as a western merely marketed for its relation to the so-popular genres of the hunt film, the railroad pic and the criminal offense pic; at that fourth dimension, at that place was no recognised genre known every bit the western into which to categorise information technology.

- ^ Grant, Barry Keith. Motion picture Genre: From Iconography to Ideology. Wallflower Press, 2007. p. seven-8

- ^ a b c Grant, Barry Keith. Moving-picture show Genre: From Iconography to Ideology. Wallflower Press, 2007. p. 8.

- ^ a b c Grant, Barry Keith (2007). Picture show Genre: From Iconography to Ideology. Wallflower Printing. ISBN9781904764793.

- ^ Stam, Robert (2000-02-21). Film Theory: An Album. Wiley. ISBN9780631206545.

- ^ Truby, John. "What's My Genre?". Writers Store . Retrieved 2007-07-31 .

- ^ Ward, Lewis. "Interview: John Truby on Screenwriting and Breaking In". Script Magazine. Archived from the original on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2007-07-31 .

- ^ a b Williams, Eric R. (2017). Screen Adaptation: Beyond the Basics. New York: Focal Press. ISBN978-one-315-66941-0. OCLC 986993829.

- ^ a b Williams, Eric R. (2017). The Screenwriters Taxonomy : a roadmap to collaborative storytelling. New York, NY: Routledge Studies in Media Theory and Practice. ISBN978-i-315-10864-3. OCLC 993983488.

- ^ Thompson, Kristin; Bordwell, David (2012-07-06). Moving picture Art: An Introduction. McGraw-Loma Education. ISBN9780073535104.

- ^ Lamster, Mark (2000). Architecture and Film. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 217. ISBN9781568982076.

- ^ "Other Major Film Categories". filmsite.org. Retrieved 2015-03-xiv .

- ^ Williams, Linda (Summer 1991). "Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess". Film Quarterly. 44 (iv): 2–thirteen. doi:10.2307/1212758. JSTOR 1212758.

- ^ Williams, Eric R. "How to View and Appreciate Great Movies (episode 24: Filmmaker's Vocalism and Audience Option)". English language . Retrieved 2020-06-07 .

- ^ McNair, Brian (2010). Journalists in Film: Heroes and Villains. Edinburgh University Printing. ISBN9780748634477.

- ^ Park W. What Is Moving-picture show Noir? [e-book]. Lanham, Physician: Bucknell University Press; 2011. Available from: eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), Ipswich, MA. Accessed November xix, 2017.

Farther reading [edit]

- Friedman, Lester et al. An Introduction to Movie Genres. New York: Westward. W. Norton & Company, 2014 ISBN 978-0-393-93019-one 609p.

- Grant, Barry Keith. Picture Genre Reader I, II & Iii. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986, 1995, 2003

- López, Daniel. Films by Genre: 775 categories, styles, trends, and movements defined, with a filmography for each. Jefferson, Due north.C.: McFarland & Co., 1993 ISBN 0-89950-780-8 495p.

- Summers, Howard. The Guide To Picture show Lists 2: Genres, Subjects and Themes. Borehamwood: Howcom Services, 2018 ISBN 978-one-982904-72-ii 418p.

External links [edit]

- Genres of picture show at the Cyberspace Movie Database

- Genres and Themes, BFI screenonline

- Finding Books on Film Genres, Styles and Categories, Yale Academy Library

- "A Semantic/Syntactic Approach to Film Genre", past Rick Altman] SCRIBD academia.edu (PDF)JSTOR 1225093

- "Review: Movie/Genre by Rick Altman", by Leger Grindon. JSTOR 1213754.

armstrongunclefor.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Film_genre

0 Response to "What Kind of Film Did Critic Rick Altman Call the Most Complex Art Form Ever Devised?"

Post a Comment